Trekking Burchell's Wagon Route

Wednesday, 4th May 2016

Country Life 4 May 2016 - Pictures: Marion Whitehead

Fancy a four-year camping trip across the Southern African wilderness? The great explorer William Burchell did just that 200 years ago. Marion Whitehead follows his wagon tracks along one of the trek’s most difficult sections, the Garden Route…

There must have been days when it rained and water trickled down William Burchell’s neck as he huddled inside his specially adapted kakebeenwa (jawbone ox wagon, named for its shape of an ox jawbone). I yell as I dodge another drip and reach for my wide-brimmed hat. I’m travelling with veteran 4×4 enthusiast Katot Meyer of Oudtshoorn in his 1967 Land Rover, through the drizzle coming off the Outeniqua Mountains, and the canvas roof is beginning to leak.

“Oh no, Burchell stayed dry,” chuckles Katot, “but then his canvas was only four-and-a-half years old. This is 38 years old – that’s the difference.”

Using old maps, we’d traced Burchell’s remarkable four-year, 7 000-kilometre route and join it in the Langkloof valley where the Old Wagon Road rumbles in from the Eastern Cape on what is now Route 62. Burchell was a multi-talented botanist and naturalist who documented more Southern African species than many more-famous early travellers. He was also an excellent artist, geographer, cartographer, linguist, ethnographer, philosopher and early ecologist; even today, he remains many a nature lover’s hero.

Following in his tracks on the 200th anniversary of his trek is a way of trying to share his insights into the land – easy when we aren’t going much faster than an ox wagon in Katot’s vintage Series III Land Rover. With its 109-inch wheelbase, it’s the nearest thing to the lightweight, narrow wagon that Burchell designed for his trek across Southern Africa – except that the Landy’s roof leaks.

Our adventure began appropriately at Avontuur in the Langkloof, where farmer’s wife Annette Zondagh laughingly said she neither saw nor heard a ghostly wagon on 17 March, the anniversary of Burchell’s stay at the homestead on the farm, which has been in her husband’s family for 250 years.

On the next-door farm belonging to her brother-in-law, we drove part of the old wagon route that runs through Jimmy Zondagh’s farmyard and stop outside the old smithy where Jimmy blew a battered bugle once used to herald the arrival of the post cart. Jimmy advised us about the route ahead, much as his ancestor must have done for Burchell. From Avontuur, he said most gentlemen travellers venturing to Plettenberg Bay took a bridal path down what became Prince Alfred’s Pass, and sent their wagons with servants along the hazardous route over the Outeniqua Mountains at Duiwelskop, or one of the other passes further west.

Ever the intrepid explorer, Burchell stayed with his wagon, his plant press and the thousands of samples he had collected on his epic trek as they travelled along farmers’ sled tracks down the Keurbooms River valley to Plett. So, naturally we had to follow suit.

Which is why we’re chugging through the drizzle on the R62/N9, turning towards De Vlugt down the Joncksrus road, where the orange wild dagga blooms as profusely amid stands of white phyllica and pink confetti bushes as in Burchell’s time. Arriving at his family farm at Pietersrivier Nature Reserve, Katot shows me a stone memorial he has erected to Burchell. This is also the beginning of the trickiest part of the route, where it winds up into the brooding Outeniqua Mountains, so first we fortify ourselves with a cup of Rooibos tea.

Katot tells me how he discovered this section of Burchell’s route, now a tough 4×4 trail. “There was a huge fire that swept across the mountains. It left everything bare and I saw these tracks.” Consulting old maps – the most accurate the one made by Burchell himself – Katot realised this was the great explorer’s actual route, so for the next 10 kilometres we are sure of following in his wagon’s ruts.

Climbing the rocky route in low range is painfully slow and I get to study the waboom proteas that must have fascinated the avid botanist.

“Do you think Burchell would have gone any faster?” I ask as the Landy jolts over yet another boulder. “Oh, he passed us long ago,” chuckles Katot, “he’s got plenty of oxen pulling his wagon.”

Down the other side of the first, fragrant, fynbos-covered foothill, the Land Rover tilts alarmingly towards a muddy stream and I instinctively throw my weight to the safer side. Katot laughs even louder once we cross the stream – it’s a mud hole where vehicles often bog down and the morning’s drizzle hasn’t made it any less sticky.

We lose Burchell’s trail jaunting down the magnificent Prince Alfred’s Pass, built by master road builder Thomas Bain in the 1860s, and branch off at Kruisvallei on the R340 to Plett to see if we can catch up with Burchell on Paardekop.

Many wagons came unstuck on this treacherous hill and early travellers left vivid accounts of its hazards. Today, the road contours around it, so we park and comb the hillside on foot for signs of wagon tracks. Katot’s finely tuned eye soon picks up a faint track and we chortle with glee as we crest the hill and take in the same vast view of forest and the blue sea that must have exhilarated Burchell.

After the long descent to the coast, Burchell camped beside the Bitou River outside Plett at Wittedrif. Hardy van Huysteen’s family has been farming at Wadrift since 1778 and he tells us that all the old explorers stayed here, then went down the east bank of the river and crossed at low tide, continuing past what is now the Goose Valley golf course.

Burchell arrived in Plett two months after leaving the Langkloof, and camped for nine days on the hill above Central Beach, says researcher Dr Roger Stewart. Clearly, he enjoyed the Garden Route as much as modern holidaymakers do, as he stayed for another three months at Melkhout Kraal in Knysna, very close to the grave of his former host George Rex, the country squire rumoured to have been King George III’s illegitimate son. Burchell also identified and collected snakes, insects and birds in the Knysna area, including the famous Knysna Turaco.

The sun’s setting when Katot and I find Westford Nature Reserve, where Burchell crossed the Knysna River, about two kilometres upstream from today’s bridge over the N2. He couldn’t have used Phantom Pass, built by Thomas Bain much later, but we drive it anyway, linking up with the N2 past Rheenendal.

I return another day to follow Burchell’s meanderings as he collected specimens among the vleis and lakes of picturesque Wilderness. I take the badly rutted gravel road along the northern bank of Langvlei and Island Lake, part of the Garden Route National Park, where it still feels like the Eden of Burchell’s time.

The beautiful but dreaded Touws River gorge outside Hoekwil, and the terrifyingly steep Kaaimansgat, were Burchell’s last obstacles before reaching George, then no more than a woodcutter’s outpost. He spent a month recovering from these arduous crossings at the campsite he named Sylvan Station below George Peak, which he hiked up in two days.

It’s fitting that the Garden Route Botanical Garden has been established in roughly the same area where the great botanist camped, and that a bust commemorating the bicentenary of his remarkable journey has been erected jointly by the Knysna Historical Society, the Outeniqua Historical Society, the George Heritage Trust and the Simon van der Stel Foundation.

“Burchell was the first European visitor to travel by ox wagon along the entire route from the Langkloof to Mossel Bay, via Plettenberg Bay,” says Dr Roger Stewart, who was guest speaker at the unveiling of Burchell’s bust on 19 September 2014. “He and his team successfully negotiated some of the most formidable and dreaded obstacles to travel in the Cape Colony at that time. Retracing Burchell’s journey through the Garden Route reminds us that he was the first naturalist intensively to study its flora and fauna, a contribution that has received relatively little attention.”

“Burchell was the first European visitor to travel by ox wagon along the entire route from the Langkloof to Mossel Bay, via Plettenberg Bay,” says Dr Roger Stewart, who was guest speaker at the unveiling of Burchell’s bust on 19 September 2014. “He and his team successfully negotiated some of the most formidable and dreaded obstacles to travel in the Cape Colony at that time. Retracing Burchell’s journey through the Garden Route reminds us that he was the first naturalist intensively to study its flora and fauna, a contribution that has received relatively little attention.”

It’s a fine spot to end an adventure and contemplate the achievements of this remarkable pioneer, who would have been regarded as a polymath genius had he lived today.

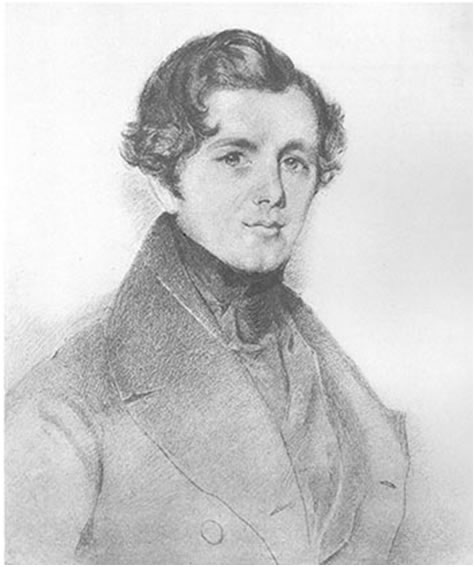

Who was William John Burchell?

- Nature lovers will recognise names such as Burchell’s zebra, Burchell’s Coucal and Burchellia bubalina (wild pomegranate), all named after the remarkable explorer and naturalist.

- Burchell travelled 7 000 kilometres of inhospitable terrain by ox wagon in Southern Africa from 1811 to 1815, going as far north as the Kuruman district, then on to the mouth of the Great Fish River before returning to Cape Town via the Garden Route.

- His collection of 63 000 specimens of flora and fauna was said to be the largest collection made by one person ever to have left Africa.

- After he returned to England, two volumes of Burchell’s Travels in the Interior of Southern Africa were published in 1822 and 1824, covering the first half of his trip. Sadly, volumes covering the rest of his trek, including the Garden Route, never appeared and have been lost to posterity.